To be sure, the Church has agreed on some basic facts, including that Jesus Christ is the living Word of God and that his atoning life, death and resurrection bring about a reconciliation between humanity and God. We affirm the lordship and

majesty of Jesus, and we give thanks for the great things God has done through the faithfulness and self-sacrifice of Jesus. There are basic truths that we as Christ's Church have been able to agree on since the coming of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost.

majesty of Jesus, and we give thanks for the great things God has done through the faithfulness and self-sacrifice of Jesus. There are basic truths that we as Christ's Church have been able to agree on since the coming of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost.Yet, while we affirm these truths, the "hows" and "whys" of these truths have continued to elude firm conclusions over the course of centuries. How - exactly - does Christ's atonement work? What - precisely - happens after we die? How does humanity's free will interact with God's sovereignty? Men and women of greater faith and intellect than me have not been able to come to final conclusions on these questions, and I do not pretend to offer authoritative answers where the great Doctors of the Church have been unable to reach a final verdict.

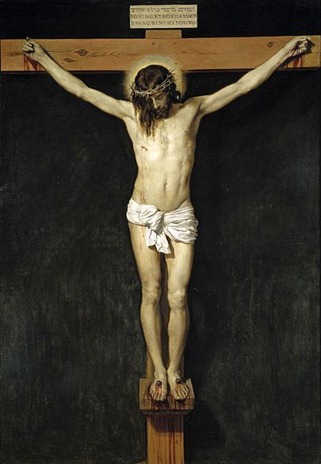

However, the fact that there are a variety of orthodox understandings of the faith does not mean that we do not have preferences. Even within the bounds of orthodoxy, we can observe that certain ideas - while not necessarily heretical - can have positive or negative effects on those who believe them. For example, the substitutionary atonement model for understanding Christ's sacrifice on the cross falls well within the orthodoxy of the Church. There is clear scriptural support for this perspective, and

generations of Christians have understood God's grace through this lens. Despite the validity of this way of viewing the atonement, however, it also presents us with challenges.

generations of Christians have understood God's grace through this lens. Despite the validity of this way of viewing the atonement, however, it also presents us with challenges.One major problem is that some versions of the substitutionary atonement model understand Jesus as enduring God's wrath, taking the punishment that God the Father would have otherwise poured out on us. This is a very disturbing image, reminiscent of the domestic abuse that takes place in many families. If we are to take this model of the atonement seriously, we must wrestle with its shadow side, which, left unexamined, could validate an image of God as abusive Father and Husband.

On the other hand, there are many other orthodox perspectives of the atonement. One that is a favorite among liberal, orthodox Christians is the moral influence model. This model, which finds ample support in the early Church, understands Jesus' atoning work as being primarily about the example of love and self-sacrifice that he set for us. Just like the substitutionary model, there are attractive aspects to this theory. However, the moral influence theory also has its shadow side: If this is the only lens we bring to our understanding of the meaning of Christ's work, we are at risk

of downplaying or ignoring the spiritual reality of his suffering and death on the cross. It is not enough to simply follow the teachings of Jesus - we must also be baptized into his suffering and death.

of downplaying or ignoring the spiritual reality of his suffering and death on the cross. It is not enough to simply follow the teachings of Jesus - we must also be baptized into his suffering and death.With all of the various orthodox models for understanding the atonement (and there are many), I would argue that we cannot choose just one. In fact, I would urge you to consider that it is the atonement itself that is the foundation of our faith as Christians, not theories about how it works. These theories are valuable as we seek greater understanding of the faith that we have received through Christ's life, death and resurrection; but theories cannot replace the wordless reality that is the living power and presence of the Holy Spirit. When we begin to battle over which theory of the atonement is the right one, we have already missed the point.

You might be wondering at this point why I am giving such a detailed treatment of atonement theory in a post that is ostensibly about Christian Universalism. My reason is this: I believe that Universalism is a model for understanding the purpose and effects of the atonement, and I suspect that Universalism falls within orthodox Christianity. Nevertheless, it clearly has a rather sizable dark side that can be a threat to the integrity of our faith. Even if Universalism is not heretical per

se, is it possible that it represents the edge of one slippery slope into beliefs that undermine the foundations of our faith?

se, is it possible that it represents the edge of one slippery slope into beliefs that undermine the foundations of our faith?Some folks I respect seem to think so. My good Friend, Scott Wells, who is himself a Universalist Christian minister, pointed out in a recent blog post that Universalism seems to often be a stepping stone into more troubling doctrines. He even referred to Christian Universalism as a "gateway doctrine," leading to, "more eccentric and esoteric forms of belief." Many of us are aware of church leaders who began to profess Christian Universalism, but soon drifted away from orthodox Christianity entirely. Is this an inevitable effect of accepting Christian Universalism? I do not believe so, since my friend Scott is still an orthodox Christian, despite having been a Universalist minister for many years.

As I continue to wrestle with these questions, I invite you to reflect along with me: Does Christian Universalism present an opening to truly heretical doctrines? If so, how can we guard against the tendency towards heresy while still affirming and embracing the universalist perspectives that have always been active within the orthodox Church?